You take your shoes off just inside the front door. Everyone knows that. Standard practice in Japanese homes and many other places besides, leaving outdoor shoes in the entryway keeps floors cleaner and provides a sense of transition between life at home and life out in the world.

But this initial change or shedding of footwear at the front door, however, may not be the only such transition, depending on one’s living situation.

NB: This is not meant to indicate how things are in homes in Japan in general, only how things are in my own. What happens there may or may not relate to what happens elsewhere.

My old apartment was simple in this way. Leave your shoes at the door and that’s it. No other changes to make

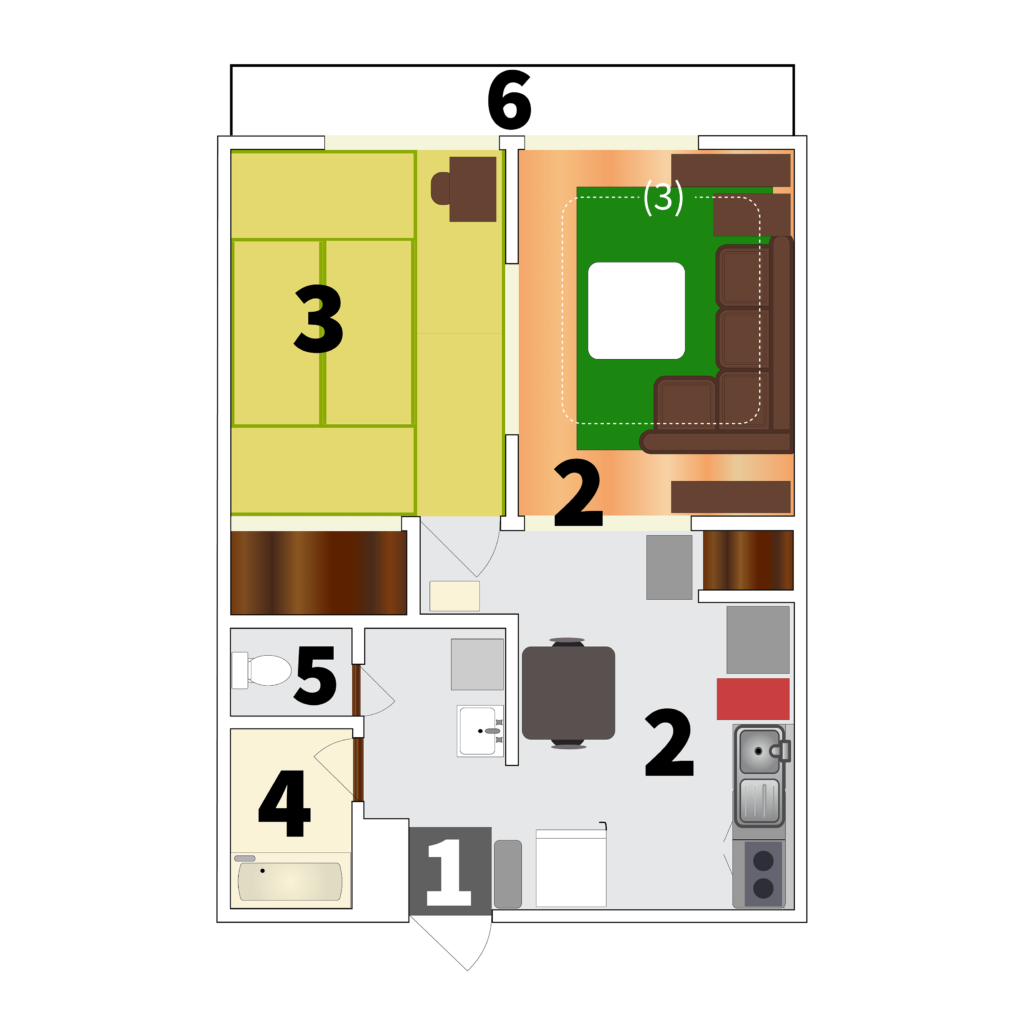

In my current apartment, though, there are six distinct footwear zones, as I see it. This is partly because it’s bigger and more complex than my old one-room shoebox, and partly because I now live with someone who has done a good job of training me in certain domestic habits.

Let’s explore the six zones.

Zone One is the entryway. About ten centimeters lower than the floor in the rest of the apartment, the genkan is the domain of shoes, umbrellas, and bicycle helmets. It is small, about 80cm square, floored with a nondescript gray tile, and flanked by shoe cabinets on either side. Outdoor shoes are welcome here, but nowhere further inside.

Zone Two is comprised of the kitchen, laundry area, and about half of the living room. Here, you’re fine with slippers, socks, or bare feet. Whatever you prefer to wear on the kitchen’s cream-colored vinyl and the living room’s medium-brown imitation hardwood.

Zone Three is more restricted, but only in that slippers are left behind at the border with Zone Two. This zone most notably includes the bedroom, with its floors of tatami—thick, firm mats covered in woven rushes. It also includes the portion of the living room with the couch, kotatsu1, and underlying area rug.

Zones Four through Six get a bit more specialized.

Zone Four is the bathroom, here meaning specifically the room with the bathtub in it. Of course, you don’t wear anything at all, let alone shoes, in the course of your ablutions, but you may want to clean in there, and the floor is often wet. So when it’s time to wash the tub before drawing a bath, you don the bath boots: oddly proportioned, bulbous rubber shoes, the sole purpose of which is to keep the bottoms of your socks dry.

Zone Five is the toilet room, where you slip into the dedicated bathroom slippers. These live in the toilet room full time, the spirit behind them being one of sanitation, to prevent the tracking-about of the unclean.

Finally, Zone Six. The balcony. A pair of cheap old rubber sandals from the ¥100 store are always out there and are primarily used when watering plants and hanging laundry to dry. The likelihood of their actually being used depends on how dirty the balcony is, how much of a rush one is in, and whether or not they have recently been soaked with rain.

All of this may sound complicated and bothersome, but in practice, it is not. At worst, it’s a bit fiddly, and hardly ever does it feel even remotely that way—basically only when you’re rushing about in a way that you really can’t blame on external factors, anyway.

Mostly, these are practical measures that help keep the home clean. In the areas most associated with rest and relaxation, in the bedroom and at the kotatsu, it also gives an extra sense of respecting the role of that space. And, as I see it, that can only make life better.

-

A low table one can sit at, which uses a blanket skirt and electric heater under it in the colder months. Very, very cozy. View the Wikipedia entry for kotatsu. ↩︎